What happens if Daniel Penny is found guilty?

What happens if Daniel Penny is found guilty?

The trial of Marine veteran Daniel Penny in the chokehold death of homeless man Jordan Neely on an F train last year has deeply divided New Yorkers about vigilante justice and NYC subway safety.

NEW YORK CITY - The trial of Marine veteran Daniel Penny in the chokehold death of homeless man Jordan Neely on an F train last year has deeply divided New Yorkers about vigilante justice and NYC subway safety.

DANIEL PENNY UPDATE: WHAT HAPPENS IF PENNY IS FOUND GUILTY?

MORE: Daniel Penny criminally negligent homicide charge explained

As jury deliberations are set to begin, here's what could happen to Penny if a guilty verdict is reached:

What happens if Penny is found guilty?

- If found guilty of second-degree manslaughter, Penny faces a maximum of 15 years in prison.

- If found guilty of criminally negligent homicide, Penny faces a maximum of 4 years in prison.

- The jury cannot convict Penny on both charges – it would either have to be just manslaughter, just criminally negligent homicide or neither.

- According to the Manhattan District Attorney's Office, there's no mandatory prison sentence in the case.

Jury deliberations could begin in Penny trial

A defense lawyer asked jurors to put themselves in frightened New York City subway riders' shoes on Monday at the trial of Daniel Penny, a Marine veteran charged with choking Jordan Neely, an irate, homeless man, to death after an outburst last year on a train. FOX 5 NY's Robert Moses has the latest.

Penny's reaction to Neely touched raw nerves and fueled debate about race relations, public safety, urban life and different approaches to crime, homelessness and mental illness. The case has also sparked demonstrations that lambasted Penny and rallies that lauded him.

Some in New York and around the country see Penny as a valiant protector of fellow subway riders who feared the erratic Neely was on the verge of violence. Others view Penny as a white vigilante who summarily killed a Black man who was in need of help.

What are prosecutors arguing? What about the defense?

On Monday, both sides gave closing arguments. Penny, who gripped Neely’s neck for about six minutes, claims he was defending fellow passengers. He has pleaded not guilty.

Prosecutors say Penny was justified in using some physical force after Neely shouted in a crowded train about being willing to die, willing to go jail or — as Penny and some other passengers recalled — willing to kill. But prosecutors argue that Penny recklessly went way too far in dealing with an unarmed man.

Featured

NYC subway chokehold: What really happened on May 1, 2023, according to witnesses, video

The incident on May 1, 2023, has deeply divided New Yorkers on what should happen next, raising questions about vigilante justice. Here's what happened on that day.

"You obviously cannot kill someone because they are crazy and ranting and looking menacing, no matter what it is that they are saying," Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Dafna Yoran told jurors.

Meanwhile, defense attorney Steven Raiser asked jurors to imagine they were on that train when Neely got on, "filled with rage and not afraid of any consequences."

"You’re sitting much as you are now, in this tightly confined space. You have very little room to move and none to run," Raiser told jurors, saying his client "put his life on the line" for strangers.

"Who would you want on the next train with you?" he asked.

During the monthlong trial, the anonymous jury heard testimony from subway passengers who witnessed Penny's roughly six-minute restraint of Neely, as well as police who responded to it, pathologists, a psychiatric expert, a Marine Corps instructor who taught Penny chokehold techniques and Penny's relatives, friends and fellow Marines. Penny chose not to testify.

Jurors watched videos recorded by bystanders and by police body cameras and saw how Penny explained his actions to officers on the scene and later in a stationhouse interview room.

Daniel Penny, seen on the subway in bystander video of the altercation. (Luces de Nueva York/Juan Alberto Vazquez via Storyful)

"I just wanted to keep him from getting to people," he told detectives, demonstrating the chokehold and describing Neely as "a crackhead" who was "acting like a lunatic."

"I'm not trying to kill the guy," he insisted.

Multiple witnesses said Neely shouted about needing food and something to drink, whipped his jacket to the floor and started screaming. They differed in descriptions of his movements and whether they were threatening. Several passengers said they were alarmed, and some were thankful when Penny subdued Neely.

Daniel Penny is seen in bystander video holding Jordan Neely in a chokehold. (Luces de Nueva York/Juan Alberto Vazquez via Storyful)

City medical examiners ruled the chokehold killed Neely. A pathologist hired by Penny’s defense contradicted that finding, saying Neely was killed by a variety of other factors.

Prosecutors noted that the veteran continued to grip Neely's neck after the train stopped and anyone who wanted to get out could do so, after bystanders urged Penny to let go, and even after Neely had been still for nearly a minute.

Penny said he wanted to protect people, "but he just didn’t realize that Jordan Neely, too, was a person whose life needed to be preserved," Yoran said. She encouraged jurors to "state with your verdict that no person’s life can be so unjustifiably snuffed out."

The defense says Penny held on because Neely tried to break loose at points and the pressure on the man's neck wasn't consistent enough to kill him.

Image taken from cell phone video showing the struggle on the subway. (Luces de Nueva York/Juan Alberto Vazquez via Storyful)

Penny wanted only to hold Neely for police, and so used a "simple civilian restraint" instead of a "textbook chokehold" that would be applied to render someone unconscious, Raiser told jurors.

"The police weren’t there when the people on that train needed help. Danny was," the attorney said.

Who was Jordan Neely?

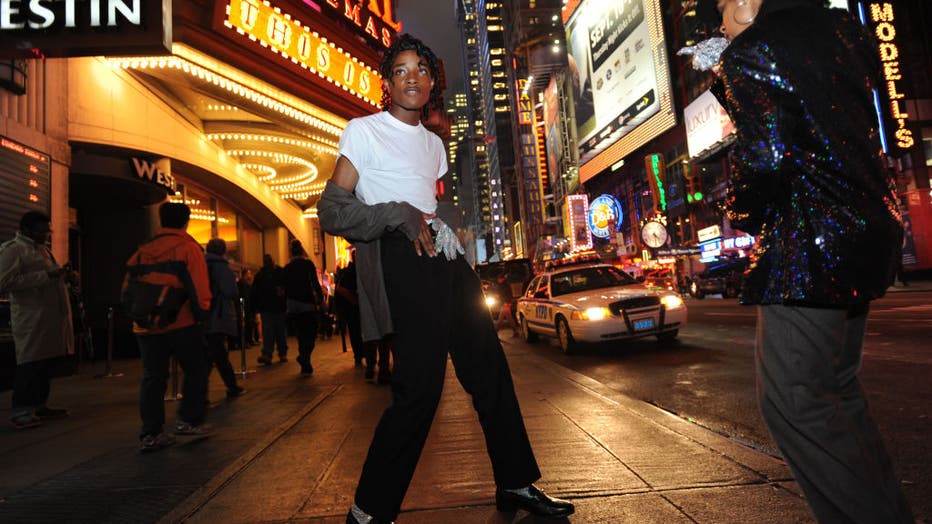

Neely once was among the city's corps of subway and street performers and was known for his Michael Jackson impersonations.

Jordan Neely is pictured before going to see the Michael Jackson movie, "This is It," outside the Regal Cinemas in Times Square in 2009. (Andrew Savulich/New York Daily News/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

But after his mother was violently killed when he was a teenager, Neely was diagnosed with depression and schizophrenia, was repeatedly hospitalized, struggled with drug abuse and had a criminal record that included assault convictions.