Running with a donkey opened Christopher McDougall's eyes about partnerships with animals

Chris McDougall and Sherman in Peach Bottom, Pa., in 2017. (Matt Roth | Courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf)

NEW YORK - Christopher McDougall is a former foreign correspondent who has reported from warzones. So he knows how to spin a yarn. But he goes much further than that by weaving that first narrative thread into a richly textured tapestry.

His first book, Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), is about the phenomenal long-distance runners from the Tarahumara tribe of Mexico's Copper Canyon. The monster best-seller became hugely influential both in and beyond the running community by helping make running barefoot (or in sandals or other minimalistic shoes) a mainstream phenomenon. (If you blame McDougall for some of the backlash to barefoot running—or even your own injuries—you probably didn’t pay close enough attention.)

Then Natural Born Heroes: Mastering the Lost Secrets of Strength and Endurance (Knopf, 2015) recounts a World War II mystery in which resistance fighters (most of whom were not professional soldiers) on the Greek island of Crete kidnapped a Nazi general and then outran and outfoxed thousands of German troops in the wilderness. Through this story, McDougall explores how strength, bravery, and endurance are linked to natural human movement, nutritional efficiency, and more.

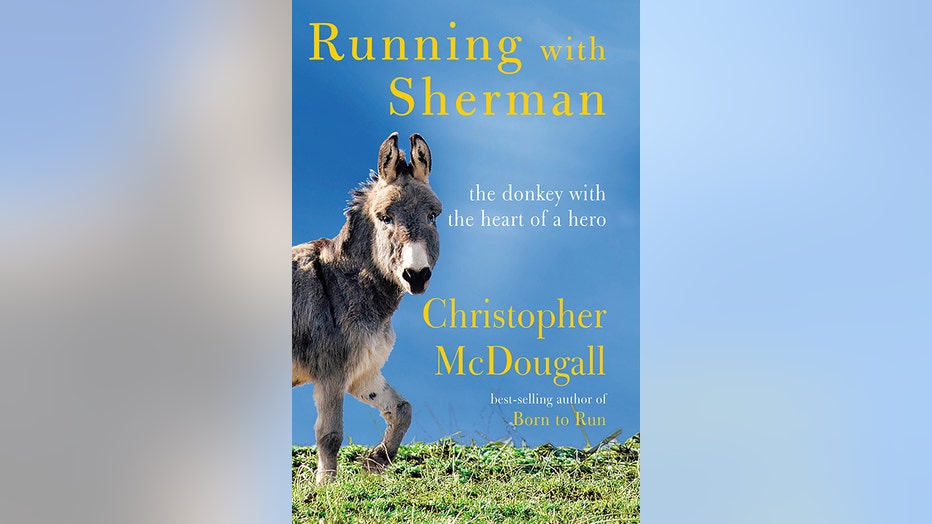

McDougall’s latest book, his most personal, tells a story set in his backyard, literally. Running with Sherman: The Donkey with a Heart of a Hero (Knopf, 2019) chronicles his journey of rescuing a severely ill and injured donkey (the aforementioned "Sherman") from an animal hoarder, helping to nurse him back to health, and teaching the beast how to run—together. As they trained for a long-distance human-and-donkey footrace (a.k.a. pack burro race), McDougall discovered some things about the nature of human-animal partnerships—and himself. (Story continues)

Chris and Sherman run through the woods. (Matt Roth | Courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf)

Although I wasn’t recovered in time from foot surgery to join McDougall on a group run he led in Brooklyn during his book tour last fall, I did speak to him by phone about this delightful tale. Here is our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity.

How did you realize that this story, Sherman's story, was, in fact, a book?

CHRISTOPHER MCDOUGALL: This is a weird story that found me rather than me finding the story. My daughter had this idea that she wanted a donkey for her 10th birthday. And when I started asking around, one of our neighbors out here in rural Pennsylvania said, yeah, he knew someone that had a donkey and is actually in a bad situation. And so we ended up adopting a rescue donkey and discovering that we needed to rehabilitate it by teaching it how to run because he'd been immobile for so long. So he needed a way to get out and get moving. And it was because of that that I started looking at this whole world of the lost art of animal-human partnerships. And that's basically what the whole story became—this adventure story examining how humans used to partner one-on-one with teammates that were animals. (Story continues)

---------

Get breaking news alerts in the FOX5NY News app. It is FREE! Download for iOS or Android

---------

What are some of the things that surprised you to learn that? I loved how you weaved in stories that weren't even about Sherman but were about these other ways in which humans and animals were partners.

CHRISTOPHER: Like most people, I always sort of took this animal companionship for granted and I assumed that animals were these pets, these furry accessories that we kept in our back bedrooms and took out for walks while we check our phones. What I didn't really comprehend was how crucial this partnership with animals has been for much of human existence.

And not only did we learn from animals but we really relied on them for so many crucial aspects of human development. It was an animal that taught us how to hunt, how to navigate, how to adapt to different terrains. Without domesticated packs and horses, we would not have expanded and explored as much as we have as a species. And the key to that, though, is learning how to empathize and communicate with the nonverbal creature. (Story continues)

Chris tries to ease Sherman through his fears. (Matt Roth | Courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf)

What was one of the things that frustrated you the most when you were rehabbing Sherman and learning to run with him? And what do you think he was frustrated most with you about, if you could discern that?

CHRISTOPHER: I came into this with the conception that donkeys are stubborn. And early in the process, I realized I'm sure donkeys look at us and feel the same way about us, that we were the stubborn ones. Because the thing about donkeys and humans is that as species, we're actually surprisingly similar. We are both species that like to think and make logic-based conclusions for ourselves.

And that's why donkeys have this reputation of being stubborn. They don't want to be forced to do anything. They want to think and contemplate and make a reasoned decision on their own. And that's what really separates them from horses. Horses have a flight instinct; when a horse is afraid, it'll try to run away. But donkeys are different. When a donkey's afraid, it will lock down and freeze up and assess the situation before it makes a move, which I think is actually similar to most humans.

That's kind of what we do. And so when you have two creatures that are both trying to make their own decisions, that can lead to a good bit of frustration on both sides.

Besides the human-animal partnership in terms of working together, what would you say is its mental health aspect? I'm not trying to pry into your own business but did you find that you got something out of this that was beyond just the physical?

CHRISTOPHER: I don't think it's any coincidence is that if you bring an animal into any hospital setting—if you bring a dog, for instance, into a cancer ward, you'll automatically find that the need for pain medication, for instance, drops in half, that your stress and anxiety levels drop in half.

I think we are physiologically hardwired to respond positively to any kind of animal contact, which makes sense, of course. If we relied on animals for our survival for so long then our brains would evolve to encourage this kind of behavior, this kind of relationship, because it was good for the species. And so that's why if a dog shows up in any room, the dog is suddenly the focus of everyone's attention. Say, with a cat: everyone wants to touch it and pet it. For a reason: because we physiologically had a positive response to that.

And that's basically what happened with me—I found two things. One was I had to shelve my own frustrations, expectations, my own demands because you just can't do that with nonverbal creatures. If you're going to partner with them, you got to learn to watch it think and empathize. And the second thing was, I was getting this daily dose of calming endorphin surges just by having contact with creatures for two or three hours a day. It was almost like a natural, holistic burst of healing medication every day. (Story continues)

Kip, Chris and Sherman on a pre-race run. (Mika McDougall)

You're a bigger character in this book than you are in your prior two books. In Born to Run and Natural Born Heroes, you wove yourself into the narrative but this one is very much more about you. Was that scary? Was that fun? Was that just a natural progression of your writing?

CHRISTOPHER: It was a little of all of those. It was a natural progression in two senses. My editor at Knopf has been pushing me to do this since we started working together on Born to Run. Even for Born to Run, I'm a much more visible presence in that book only because my editor really pushed me. I have a hard-news tradition where there is no first-person pronoun; you never say the word "I."

So I pushed back saying, "Look, I'm the least interesting guy in these stories." And he said, "That's the point. You're the access point. You're the reader's proxy and that's why you need to be there."

The second thing was that when you do a book, you have so much ground to cover. You got to decide on page 1 whose story is this? Who are we tracking? In Running with Sherman, it's me. So it's kind of unavoidable.

What's been the response so far?

CHRISTOPHER: It's been crazy. People are so passionate about the story. A lot of people who come [to public events] who don't really know what the book's about are so excited about a positive, feelgood story about an animal. Even before they've read it, they're excited. [Then there are] people who've read it and feel so personally attached. They really want to share that. Everyone at these events has been emotional—much more emotional and energetic than any other events I've ever done. (Story continues)

Sherman the donkey on his first morning in Colorado. (Christopher McDougall)

I've been reading the book while listening to your narration in the audiobook version. It's kind of awesome to hear you personally narrate this book. Has anyone given you feedback about the audiobook?

CHRISTOPHER: I've been getting a lot of feedback about that. And I'm really curious because not only did I not narrate either the other two books, but for Natural Born Heroes, I picked a British narrator because I knew his work from all the books he's done. I thought, "This guy's really, really good." But the audio editor said, "Hey, but he's British and you're not." I said, "I know—he's really good."

So that's how far removed I've been from it. So this is the first time I tried it and I'm really kind of curious to hear what the responses are. So far, people have been extraordinarily complimentary. But I still have not knuckled down and listened to it myself. I'm kind of waiting for that moment to listen to myself.

Your readers and fans have come to know your voice, literally, because of podcasts, radio interviews, TV interviews, and in-person appearances. So people who follow you know how you sound. This seems like a natural progression, especially since this is the most personal of your three books so far.

CHRISTOPHER: Which also made it difficult because it was hard to do. I found myself getting emotional, really kind of choking up as I was reliving some of these parts.

Any final thoughts about your experiences with Sherman?

CHRISTOPHER: One thing that kept coming up with me as we were trying to both train the donkeys and train ourselves for this race: people are too hard on themselves. We set these standards for what we have to be doing in terms of our training and our obligations in life.

What I found with the donkeys is, you're going make mistakes all the time and so you just get over them and move on. But a lot of times I talk to people about their own running. They're always apologizing. "I didn't train enough." "I'm not going fast enough." "I didn't meet my goals."

And that's the one thought I took away from this adventure with the donkeys is: Just stop apologizing, stop feeling bad. And what you do and what you get—that's the best to be hoped for.

Follow Chris on Twitter. Watch him run with Sherman.

Arun Kristian Das is a senior digital content creator for FOX 5 NY and a running coach. He doesn’t have a donkey to help him recover from foot surgery but he just might teach his cat to go hiking. Follow him on Twitter.

The cover for "Running with Sherman: The Donkey with a Heart of a Hero" by Christopher McDougall (Courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf)